No 165: Policy making and evidence selection

Dr Adrian Davis

Top line: Political pressures may encourage a selective use of evidence as a rhetorical device to support pre-determined policy choices or ideological positions. Such biases are likely to be amplified when there is a lack of institutional capacity or structures able to provide competent and independent scientific advice. 1

Policy making takes place in the context of uncertain conditions and increasingly complex policy problems. At the same time, there is an often stated desire among policy makers to formulate policies based on the best available evidence. But the evidence has to align with what Kingdon 2 called ‘the political stream’. This is the standpoint of politicians, composed of such things as ‘public mood’, pressure group campaigns, election results, and which Party holds power in government.

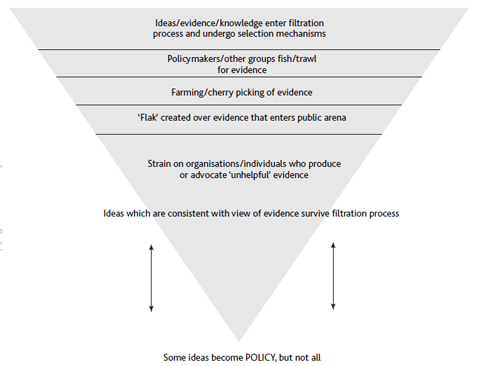

This stream is based on consensus and compromise so that evidence-based proposals may be weakened through any processes of negotiation. For evidence developed by officials to be used in policy it has to survive attempts in the ‘problem’ stream to filter it out (Figure. 1), a process which is achieved by finding powerful sponsors who advocate particular kinds of evidence in policy.

Evidence which survives the various filtration mechanisms stands the best chance of being used in policy.3 Proposals that meet several criteria enhance their chance of survival. As Kingdon noted, conditions must often deteriorate to crisis proportions before the subject achieves enough visibility to become an active agenda item. In the UK, action to address poor air quality and the threat of legal sanction or fines in motivating governments to take action to protect human health might be an apposite example of policy intervention via crisis.

1 Liverani, M., Hawkins, B., Parkhurst, J. (2013) Political and Institutional Influences on the Use of Evidence in Public

Health Policy. A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 8(10): e77404.

2 Kingdon, J. 1995 2nd (ed) Agendas, alternatives, and public policies, New York: HarperCollins.

3 Stevens, A, 2007, Survival of the ideas that fit: An evolutionary analogy for the use of evidence in policy, Social Policy

and Society 6, 1, 25–35

4 Ingold, J., Monaghan, M. 2016 Evidence translation: an exploration of policy makers’ use of evidence, Policy and

Politics, 44(2): 171-190.